Quick Navigation

- Introduction to Differential Signaling

- Why Differential Signaling Matters

- Understanding Differential Pair Fundamentals

- Common Differential Signal Standards

- Critical Placement Considerations

- Differential Pair Routing Rules

- Differential Pair Routing Guidelines

- Differential Routing Best Practices

- Advanced Routing Techniques

- Common Design Challenges and Solutions

- Design Verification and Testing

- Modern Automation in Differential Design

- Conclusion and Best Practices Summary

- Frequently Asked Questions

Introduction to Differential Signaling

In today's high-speed digital world, differential signaling has become essential for reliable data transmission in PCB designs. From USB and Ethernet to high-speed memory interfaces and display connections, differential pairs are everywhere in modern electronics. Understanding how to properly place and route these critical signals can make the difference between a working design and one plagued by signal integrity issues.

This comprehensive guide covers the fundamental principles, practical considerations, and modern approaches to differential pair design, including insights from automated placement and routing techniques that are changing how engineers approach complex layouts.

Why Differential Signaling Matters

Differential signaling offers significant advantages over single-ended signals:

- Superior noise immunity: Common-mode noise affects both traces equally and cancels out

- Reduced EMI emissions: Equal and opposite currents minimize electromagnetic radiation

- Better signal integrity: Controlled impedance and balanced transmission

- Higher data rates: Enables faster switching speeds with cleaner signals

- Lower power consumption: Smaller voltage swings reduce power requirements

Understanding Differential Pair Fundamentals

What Are Differential Pairs?

A differential pair consists of two complementary signals (often labeled P and N, or + and -) that carry the same information but with opposite polarity. The receiver detects the voltage difference between these two signals rather than their absolute voltage levels. This approach provides inherent noise rejection because any noise that affects both traces equally (common-mode noise) is ignored by the differential receiver.

Key Electrical Parameters

| Parameter | Typical Values | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Impedance (Zdiff) | 90Ω, 100Ω, 120Ω | Impedance between the two traces in the pair |

| Common-Mode Impedance (Zc) | 25-60Ω | Impedance of each trace to ground |

| Coupling Coefficient (k) | 0.1-0.3 | Degree of electromagnetic coupling between traces |

| Skew Tolerance | ±10% of rise time | Maximum acceptable delay mismatch |

Key Relationships:

Where Z0 is the single-ended impedance and k is the coupling coefficient

Common Differential Signal Standards

Different protocols require specific impedance values and design considerations. Here's a comprehensive overview of common differential signal standards:

| Protocol | Differential Impedance | Tolerance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| USB 2.0 | 90Ω | ±15% | Skew ≤150 ps (≈2.5 mm), short stubs, maximum 3m cable length |

| USB 3.0/3.1 | 90Ω | ±7% | Tight skew requirements ≤25 ps, strict impedance control, separate from USB 2.0 pairs |

| Ethernet 10/100 | 100Ω | ±5% | Transformer isolation required, moderate skew tolerance |

| Gigabit Ethernet | 100Ω | ±5% | Strict skew requirements ≤100 ps, all 4 pairs must be matched, ground plane continuity critical |

| HDMI | 100Ω | ±15% | Multiple differential pairs (TMDS), skew ≤40 ps within pair, ESD protection needed |

| PCIe Gen1/2 | 85Ω | ±7% | Skew ≤20 ps, AC coupling required, strict layer stackup requirements |

| PCIe Gen3/4 | 85Ω | ±5% | Very tight skew ≤10 ps, loss budget critical, requires simulation validation |

| SATA | 100Ω | ±15% | AC coupling caps required, ground plane under traces, via count minimization |

| DDR4 | 100Ω (clock, DQS) | ±10% | Topology-dependent routing, on-die termination, fly-by architecture for address/command |

| DDR5 | 80-100Ω (varies) | ±8% | Higher speeds require tighter control, decision feedback equalization impacts design |

| LVDS | 100Ω | ±10% | Low voltage swing (±350mV), excellent EMI performance, common in displays and cameras |

| CAN Bus | 120Ω | ±10% | Termination resistors required at both ends, robust to EMI, automotive applications |

| DisplayPort | 100Ω | ±10% | Multiple lanes, auxiliary channel separate, pre-emphasis and equalization support |

| MIPI D-PHY | 100Ω | ±15% | Mobile display/camera interface, LP (low power) and HS (high speed) modes |

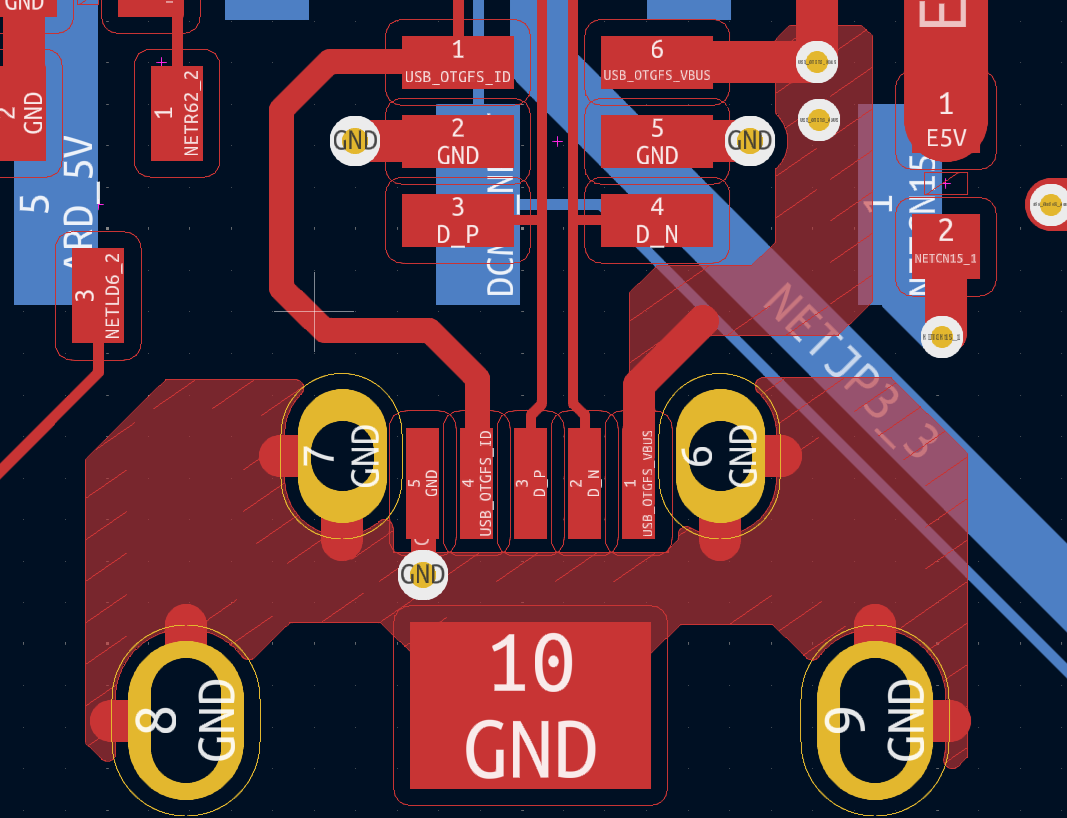

Critical Placement Considerations

Component Proximity and Grouping

Proper placement is the foundation of successful differential routing. The physical arrangement of components directly impacts signal integrity, routing complexity, and overall design success.

Strategic Placement Guidelines

- Minimize trace lengths: Place differential sources and loads as close as possible

- Group related components: Keep all components for a differential interface together

- Consider pin escape: Ensure differential pins can exit components cleanly

- Plan layer transitions: Minimize via count in differential paths

- Isolate sensitive circuits: Keep high-speed differential away from sensitive analog

- Account for termination: Reserve space for termination resistors and AC coupling

Connector and Interface Placement

Connector placement significantly impacts differential routing success. Modern automated placement algorithms consider multiple factors simultaneously:

💡 Pro Tip: Automated Placement Intelligence

Advanced placement algorithms analyze pin assignments, trace length requirements, and layer escape strategies to optimize connector positions. This multi-constraint optimization often yields better results than manual intuition alone, especially for complex boards with multiple differential interfaces.

✅ DO

- Position connectors for short, direct paths

- Align differential pins for parallel routing

- Consider mechanical constraints early

- Plan for proper ground references

- Group related differential interfaces

❌ DON'T

- Place connectors without considering routing

- Ignore pin assignment optimization

- Create unnecessary layer transitions

- Split differential interfaces across board

- Overlook return path requirements

Differential Pair Routing Rules

Keep the two traces tightly coupled and parallel, reference the same continuous return plane, and keep any uncoupled stubs as short as possible. Co-locate vias in pairs, minimize layer transitions, and match lengths within your skew budget computed from the stackup.

Essential Routing Rules

- Net Naming: Define pairs with a clear suffix (_P/_N) and put them in a net class

- Via Management: Keep same number of vias on P and N; place stitching vias near any plane transition

- Route Geometry: Prefer straight routes; if you must meander, meander both partners

- Uncoupled Length: Enforce maximum uncoupled length (breakouts, pads, test points)

- Impedance Control: Use stackup-based width/gap (not "rules of thumb") for target Zdiff

Differential Pair Routing Guidelines

Choose width/gap from your stackup to hit the required Zdiff (e.g., 90Ω USB HS, 100Ω Ethernet/PCIe/LVDS). Route over a single reference plane per segment; if you must cross a split, provide a stitching path for the return current within ~1–2 mm.

Critical Guidelines

- Reference Planes: Avoid reference plane gaps; if unavoidable, bridge with stitching capacitors/vias as appropriate

- Pair-to-Pair Spacing: Keep pair-to-pair spacing ≥ 3× the intra-pair gap to reduce crosstalk

- Layer Selection: Prefer microstrip for short, simple runs; prefer stripline for dense, noisy boards

- Connector Breakouts: Treat connector breakouts like controlled impedance features; follow vendor land patterns

Differential Routing Best Practices

Trace Geometry and Spacing

The physical geometry of differential traces directly affects their electrical performance. Proper spacing, width, and layer selection are crucial for maintaining target impedance and ensuring reliable signal transmission.

Critical Routing Parameters

Spacing Calculations:

Center-to-center spacing = W + s

Where W = trace width

Length Matching Requirements

Maintaining proper length matching between differential pair traces is essential for signal integrity. Different protocols have varying tolerance requirements:

| Protocol | Skew Tolerance | Matching Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| USB 2.0 | ±150 ps | ±2.5mm at PCB level |

| USB 3.0 | ±25 ps | ±0.1mm (very tight) |

| Gigabit Ethernet | ±100 ps | ±1.5mm at PCB level |

| PCIe Gen1/2 | ±20 ps | ±0.3mm within pair |

| HDMI | ±40 ps | ±0.6mm within pair |

Layer Transitions and Via Management

Differential signals often need to change layers, requiring careful via placement and return path management.

Key considerations for via transitions include proper return path management, impedance control, and minimizing discontinuities. Advanced routing algorithms can automatically handle these requirements while maintaining signal integrity.

⚠️ Via Transition Considerations

- Always transition differential pairs together (same location)

- Provide return path stitching vias nearby

- Account for via impedance discontinuity

- Minimize the number of layer transitions

- Consider stub length for non-through vias

Advanced Routing Techniques

Curved vs. Angular Routing

The choice between curved and angular routing affects both signal integrity and manufacturing considerations. Modern routing engines typically favor curved approaches for their superior electrical performance.

Routing Style Comparison

Curved Routing Advantages

- Smoother impedance transitions

- Reduced EMI emissions

- Better high-frequency performance

- More aesthetically pleasing

- Easier length matching

Angular Routing Considerations

- Impedance discontinuities at corners

- Potential EMI hotspots

- More complex length matching

- Traditional but less optimal

- Still acceptable for lower speeds

Serpentine Routing for Length Matching

When differential traces need length matching, serpentine (meandering) sections are often required. The key is using gradual curves rather than sharp corners, maintaining consistent spacing throughout serpentines, and placing them away from sensitive circuits.

💡 Serpentine Best Practices

- Use gradual curves rather than sharp corners

- Maintain consistent spacing throughout serpentines

- Place serpentines away from sensitive circuits

- Consider the impact on impedance and crosstalk

- Minimize the serpentine section length

Preferred Differential Pair Signal Gap

The "right" gap is whatever your stackup solver returns for the target impedance and selected trace width. As a quick start, many 4-layer FR-4 microstrips hit 90Ω with ~0.14–0.18 mm width and ~0.16–0.22 mm gap, but always verify with your fab's stackup.

Gap Selection Process

- Use Field Solver: Use your fab's field solver

- Lock Geometry: Lock gap and width per layer; avoid changing geometry mid-route

- Maintain Spacing: Keep pair-to-others spacing ≥ 3× gap

How to Flip Vias in Differential Pairs

Place P and N vias as a matched pair with identical antipads and keep them as close as DRC allows; route short necks into the pair to avoid length asymmetry. When changing reference planes, add a stitching via within ~1–2 mm to provide a return path.

Via Placement Best Practices

- Routing Strategy: Route into the center of the via pair; avoid doglegs on only one partner

- Via Consistency: Same via count and drill for P and N; avoid via stubs (backdrill if needed)

- Length Verification: Verify with length report: P and N through-via lengths must be matched

Test Point Placement in Differential Pairs

Avoid in-line test pads on high-speed pairs; if you must, place symmetrical pads on both P and N and keep them very small or use probe pads on a short coupled spur. Favor connector-side fixtures and AC-coupled test methods over intrusive pads.

Test Point Guidelines

- Spur Length: If you must tee off, keep the spur ≤ 1–2 mm and matched on both lines

- Integrated Probing: Consider footprint-integrated probing (e.g., header pads at connector breakouts)

Routing a 1 GHz Differential Output to Multiple Connectors

⚠️ Critical Design Constraint

Splitting a high-frequency differential pair creates stubs and impedance discontinuities. It is not recommended. If you need to do it then document expected return loss/eye degradation; validate on the SI tools of your choice.

Differential Via Transition

Treat the via pair as part of the transmission line; keep antipads/clearances consistent and add stitching vias to maintain the return path. Avoid long plated stubs (use backdrilling or blind/buried vias if available).

Via Transition Guidelines

- Via Spacing: Co-locate the pair; center-to-center distance ≈ intra-pair gap is a good start

- Plane Transitions: Keep plane transitions minimal and symmetric

Common Design Challenges and Solutions

Routing in Constrained Spaces

Modern PCB designs often face space constraints that make differential routing challenging. Proven strategies include via-in-pad techniques, blind/buried vias, layer stack optimization, and intelligent component orientation.

Space-Constrained Solutions

- Via-in-pad techniques: For BGAs and high-density designs

- Blind/buried vias: Reduce via count and improve routing density

- Layer stack optimization: Choose appropriate layer pairs for routing

- Component orientation: Rotate components for better pin escape

- Micro-via technology: Enable finer routing pitch

Managing Multiple Differential Pairs

Designs with numerous differential interfaces require systematic approaches to avoid conflicts and maintain signal integrity. This involves prioritizing critical signals, grouping by speed requirements, and maintaining proper isolation between different pairs.

Multi-Pair Design Guidelines

- Prioritize critical signals: Route timing-sensitive pairs first

- Group by speed: Separate high-speed and low-speed differential signals

- Maintain isolation: Provide adequate spacing between different pairs

- Plan layer assignments: Distribute pairs across multiple layers

- Consider crosstalk: Account for near-end and far-end crosstalk

- Validate timing: Ensure all pairs meet their timing requirements

Design Verification and Testing

Simulation and Analysis

Proper verification ensures your differential design will work reliably in the real world:

Essential Verification Steps

- Impedance analysis: Verify differential and common-mode impedance

- Crosstalk simulation: Check for excessive coupling between pairs

- Eye diagram analysis: Assess signal quality at the receiver

- Return loss analysis: Identify impedance discontinuities

- Power integrity: Ensure clean power delivery to differential circuits

- EMI compliance: Validate emissions and immunity requirements

Physical Testing Considerations

Design your PCB with testing in mind from the beginning:

- Test point placement: Provide access for differential probing

- TDR test structures: Include impedance verification features

- Loop-back paths: Enable signal integrity testing

- Debug headers: Provide access to critical differential signals

- Ground probe points: Ensure proper measurement references

Modern Automation in Differential Design

How Intelligent Placement and Routing Changes the Game

Traditional differential design requires extensive manual work and deep expertise. Modern automation tools are changing this landscape by embedding proven design practices directly into the placement and routing algorithms.

Automated Placement Intelligence

Advanced algorithms analyze connectivity, timing requirements, and physical constraints to optimize component placement for differential signals. This includes automatically clustering related components, optimizing pin escape angles, and reserving appropriate routing channels.

Intelligent Routing Algorithms

Modern routing engines can maintain precise impedance control, automatically match lengths within tight tolerances, and optimize via placement—all while respecting design rules and avoiding conflicts with other signals.

Benefits of Automation for Differential Design

- Consistency: Every differential pair gets the same level of attention and optimization

- Speed: Complex differential routing completed in minutes rather than hours

- Accuracy: Precise length matching and impedance control without manual calculation

- Best Practices: Embedded design rules ensure compliance with industry standards

- Iteration: Easy to modify and re-optimize as requirements change

Conclusion and Best Practices Summary

Successful differential signal design requires careful attention to both placement and routing decisions. The key principles remain consistent across different technologies and protocols:

🎯 Key Takeaways

- Start with placement: Good placement makes routing possible; poor placement makes it impossible

- Understand your requirements: Know the impedance, timing, and spacing requirements for your specific protocols

- Plan for manufacturing: Consider fabrication capabilities and assembly constraints

- Verify early and often: Use simulation to catch problems before fabrication

- Consider automation: Modern tools can handle much of the complexity while maintaining design quality

- Keep learning: High-speed design techniques continue to evolve with technology

Looking Forward

As data rates continue to increase and PCB designs become more complex, the challenges of differential signaling will only grow. However, advances in automation, simulation, and manufacturing are making it possible for more engineers to successfully implement high-quality differential designs without becoming signal integrity experts.

The combination of solid fundamental understanding and modern automation tools provides the best path forward for reliable, manufacturable differential signal designs in today's demanding electronic systems.

Frequently Asked Questions

Want to Know More About How We Use AI with PCB Design?

Check out our comprehensive blog covering AI-assisted PCB design verification across Altium, Cadence, KiCad and other tool series.

Blogs